Willow

Youth

Belfast is the economic engine of Northern Ireland. Europe-wide demands for national borders and the construction of walls are endangering the peace in the city as much as Brexit. This and the many decades of religious and national conflict have deeply divided Belfast's population.

Running through the west of the city, which has been particularly affected by the tensions, are two roads, Shankill Road and Falls Road, between which the presence of the old conflict is particularly evident.

Running through the west of the city, which has been particularly affected by the tensions, are two roads, Shankill Road and Falls Road, between which the presence of the old conflict is particularly evident.

Shankill Road runs through a pro-British and Protestant neighborhood, while Falls Road, in some places less than a kilometer away, runs through a Republican-Irish and Catholic neighborhood. Walls and fences several meters high, surveillance cameras and barbed wire fences separate the two neighborhoods that lie so close together. At night, the direct passages are closed, so that it is no longer possible to cross directly from one side to the other. On both sides of the border there are Belfastians today who want nothing to do with the old conflict, but for too many the memories are still too fresh and the conflict remains unresolved. Children growing up in Belfast today usually know no other life than the one between the fences and walls.

Willow Youth is a photographic statement of observations I made during my stay in the city on that situation.

While working on the series, I met with a group of women who have relatives who died in the conflict. The invited me to listen to their stories. To me, the stories seemed as if they had been penned in Hollywood, but the women's serious and bitter expressions left no doubt that they had actually lived through these experiences and probably many more. Based on my meeting with the women's group, I wrote the anecdote at the end of the photo series.

Willow Youth is a photographic statement of observations I made during my stay in the city on that situation.

While working on the series, I met with a group of women who have relatives who died in the conflict. The invited me to listen to their stories. To me, the stories seemed as if they had been penned in Hollywood, but the women's serious and bitter expressions left no doubt that they had actually lived through these experiences and probably many more. Based on my meeting with the women's group, I wrote the anecdote at the end of the photo series.

In a small room, somewhere in Belfast, I met nine elderly ladies, who had invited me to share with me their experiences and memories from The Troubles. They meet here every week to share their memories as a way to deal with their traumas.

When I entered the room, some of the ladies were laughing and chattering, while some sat quietly in their chairs. I asked them about their stories and they started to tell:

„I lost my husband. We had been married for almost twenty years. He got shot on the street during the day, along with his friends. None of them saw it coming. In all the years since nobody could tell me who had done it. The not knowing is what still haunts me. The police wouldn’t tell me if they were even looking for the murderer. He might still live on the other side.“

„We have all lost someone. We are all still waiting for the names of those responsible, we are waiting for justice. I don’t generally hate the others. But I tell you if that person, who shot my husband, was here with us in this room, I couldn’t promise you anything.”

„Yes, yes!“ said the others.

“It is not so much about Catholics and Protestants anymore. But look at the other street for example, it used to be the poorer neighborhood. Did you see it? All the shops are open, they are doing great. They get what they want, the city pays them. And I don’t say to take it away from them, but look at our street, what it has become. Every other store is closed, it wasn’t like this before. How can we trust them? Before the troubles started we had friends on the other side. Good friends. But some betrayed us, just gave information away and didn’t even warn us. And it cost us many lives. I don’t even trust the priests. They let the snipers on the church towers. They are responsible too.”

„Yes, yes!“ said the others.

“One time some men attacked a bus. They warned their people first, let them leave the bus and then killed the rest. They say that the police even found fingerprints. But they never investigated. We might never know who it was. We want more attention. Look, when something happens in the US it‘s all over the news. When something happens in Belfast nobody cares. The politicians do nothing.”

„No, no!“ said the others.

“During the troubles one had to show their bags when entering a shop. Plastic bags were put on street lights to avoid being spotted by snipers. I visited a friend one day, and when I got to her house I found at least seven badly wounded men at her house. She tried to help them, wash their wounds. There was blood everywhere. Once you see something like that you will never be able to forget.”

„No, no!“ said the others.

“That’s all so negative. We still like to laugh a lot. Maybe it is our way to deal with the whole thing. Let me tell you a funny story. I was coming back from the center of the city one day, I didn’t know what was going on here. When I entered the neighborhood I saw my friend Rebecca, she was waving her hands at me from the other side of the street. There were sharpshooters somewhere in the area. She wanted to warn me, but I didn’t understand her, so I waved back at her. Can you imagine? The two of us in the middle of the street waving our hands at each other and the sharpshooters above our heads?”

All of them laughed.

“See? Thats our Belfast humor.”

– Belfast, 2017

When I entered the room, some of the ladies were laughing and chattering, while some sat quietly in their chairs. I asked them about their stories and they started to tell:

„I lost my husband. We had been married for almost twenty years. He got shot on the street during the day, along with his friends. None of them saw it coming. In all the years since nobody could tell me who had done it. The not knowing is what still haunts me. The police wouldn’t tell me if they were even looking for the murderer. He might still live on the other side.“

„We have all lost someone. We are all still waiting for the names of those responsible, we are waiting for justice. I don’t generally hate the others. But I tell you if that person, who shot my husband, was here with us in this room, I couldn’t promise you anything.”

„Yes, yes!“ said the others.

“It is not so much about Catholics and Protestants anymore. But look at the other street for example, it used to be the poorer neighborhood. Did you see it? All the shops are open, they are doing great. They get what they want, the city pays them. And I don’t say to take it away from them, but look at our street, what it has become. Every other store is closed, it wasn’t like this before. How can we trust them? Before the troubles started we had friends on the other side. Good friends. But some betrayed us, just gave information away and didn’t even warn us. And it cost us many lives. I don’t even trust the priests. They let the snipers on the church towers. They are responsible too.”

„Yes, yes!“ said the others.

“One time some men attacked a bus. They warned their people first, let them leave the bus and then killed the rest. They say that the police even found fingerprints. But they never investigated. We might never know who it was. We want more attention. Look, when something happens in the US it‘s all over the news. When something happens in Belfast nobody cares. The politicians do nothing.”

„No, no!“ said the others.

“During the troubles one had to show their bags when entering a shop. Plastic bags were put on street lights to avoid being spotted by snipers. I visited a friend one day, and when I got to her house I found at least seven badly wounded men at her house. She tried to help them, wash their wounds. There was blood everywhere. Once you see something like that you will never be able to forget.”

„No, no!“ said the others.

“That’s all so negative. We still like to laugh a lot. Maybe it is our way to deal with the whole thing. Let me tell you a funny story. I was coming back from the center of the city one day, I didn’t know what was going on here. When I entered the neighborhood I saw my friend Rebecca, she was waving her hands at me from the other side of the street. There were sharpshooters somewhere in the area. She wanted to warn me, but I didn’t understand her, so I waved back at her. Can you imagine? The two of us in the middle of the street waving our hands at each other and the sharpshooters above our heads?”

All of them laughed.

“See? Thats our Belfast humor.”

– Belfast, 2017

Between the Lines

"Photography and Reflections

from Belfast"

Exhibition at Gallery Mitte, Bremen

April 13 until May 13 2018

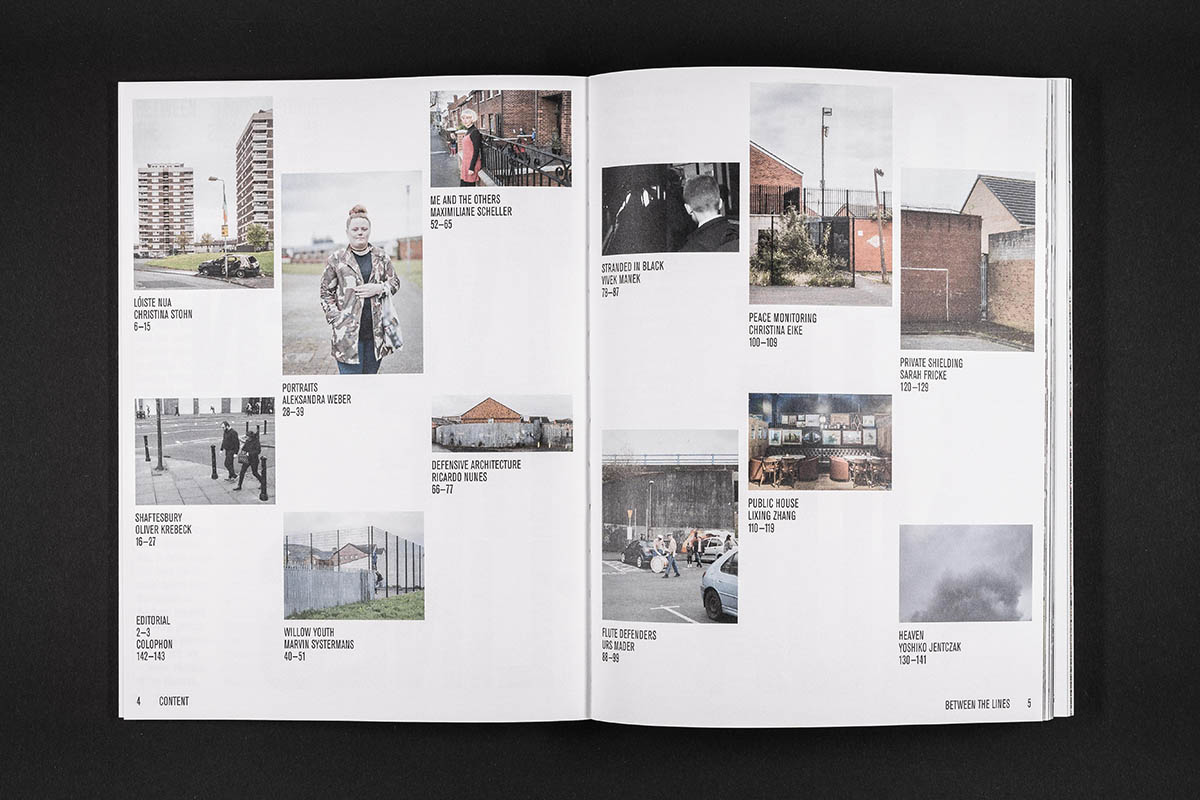

With artists:

Christina Stohn / Aleksandra Weber / Maximiliane Scheller / Riccardo Nunes / Oliver Krebeck / Marvin Systermans / Vivek Manek / Christina Eike / Sarah Fricke / Lixing Zhang / Urs Mader / Yoshiko Jentczak

"Photography and Reflections

from Belfast"

Exhibition at Gallery Mitte, Bremen

April 13 until May 13 2018

With artists:

Christina Stohn / Aleksandra Weber / Maximiliane Scheller / Riccardo Nunes / Oliver Krebeck / Marvin Systermans / Vivek Manek / Christina Eike / Sarah Fricke / Lixing Zhang / Urs Mader / Yoshiko Jentczak

© Marvin Systermans — Berlin